The Compass Rose of Perspective: Reinterpreting Maritime History

The scent of aged wood, the delicate rasp of a chisel, the patient unfolding of a plan – these are the sensations that draw us to the world of wooden model ships. More than just a hobby, it's a profound act of connection to the past, a tangible link to the mariners, shipwrights, and the very spirit of exploration that shaped our world. But as we meticulously recreate these vessels, we are doing something far more vital than simply building a miniature replica; we are engaging in a quiet act of historical reinterpretation. We are, in essence, recalibrating the compass rose of our understanding.

For centuries, historical accounts of ships and voyages have been filtered through the lenses of power, privilege, and perspective. The narratives we inherit are often those of the victorious, the wealthy, and the literate. The voices of the sailors who toiled in the rigging, the artisans who painstakingly crafted the timbers, the Indigenous peoples whose knowledge guided voyages across uncharted waters – these voices are often muted, distorted, or entirely absent. We read of Captains Cook and Magellan with awe, glossing over the complexities of their actions, the exploitation that underpinned their explorations, and the profound impact on the lives of those they encountered.

My own journey into model ship building began, somewhat unexpectedly, with a fascination for antique accordions. My grandfather, a quiet, reserved man, had a small collection, each a testament to a bygone era of music and travel. He rarely spoke about them, but I sensed a deep reverence, a recognition of the human effort and artistry embedded within their bellows and keys. It was through these accordions that I first began to appreciate the concept of tangible history, of holding in your hands something imbued with the stories of countless lives. That appreciation blossomed into a desire to understand the context – who built them, why, and what journeys did they witness?

Similarly, the world of wooden model ships offers a unique opportunity to challenge the conventional narratives. When we painstakingly recreate a 17th-century galleon, we're not just assembling a kit of pre-cut pieces. We’re delving into the complexities of shipbuilding technology, the logistics of maritime trade, and the social hierarchies that defined life aboard ship. We grapple with the challenges faced by the shipwrights – sourcing the right timber, bending the frames, ensuring watertight seams – a process far more demanding than many historical accounts would lead us to believe. Suddenly, the heroism attributed to the captain seems a little less dazzling when we’re wrestling with the intricacies of rigging a miniature topsail.

Consider the Santa Maria, Columbus’s flagship. Popular portrayals often present it as a simple, almost crude vessel, a testament to the relatively nascent state of European shipbuilding at the time. However, a closer look – and the process of building a detailed model – reveals a ship far more sophisticated than commonly perceived. The intricate construction of the hull, the careful arrangement of the deck cargo, the subtle nuances of the rigging – all speak to the skill and expertise of the shipbuilders. We begin to appreciate that it wasn’t just Columbus who achieved a monumental feat; it was the entire team of artisans and laborers who made his voyage possible.

The process of building a model also invites us to consider the perspective of those who were impacted by these voyages – those whose lives were irrevocably altered by the arrival of European ships. The historical record is often silent on their experiences, focusing solely on the actions of the explorers. But as we reconstruct these vessels, we can begin to imagine the fear, the confusion, and the trauma that they must have felt. The model becomes a vessel not just for cargo and passengers, but also for empathy and understanding.

Restoration and collecting, closely linked to the model-building world, further enrich this nuanced perspective. Examining antique plans, charts, and even remnants of original ships reveals surprising details – evidence of repairs, modifications, and alterations reflecting the evolving needs and technologies of the time. A seemingly straightforward ship plan might reveal a hidden compartment, a hastily applied patch, or a subtle change in design indicating a unique incident or adaptation.

The craftsmanship itself deserves deeper consideration. The skill required to shape and join the timbers, to carve the figureheads, to weave the rigging – these were the domains of highly specialized artisans, often overlooked in the grand narrative of maritime history. Their contributions, their knowledge, and their artistry were essential to the success of any voyage. We see their legacy etched into every plank, every knot, every curve of the hull. Building a model isn’s just replicating a structure; it’s honoring their skill and dedication.

The availability of historical plans and resources has also dramatically improved over the years. While many kits are designed for relative ease of assembly, a dedicated modeler can delve into primary source materials – original ship plans, logbooks, and even accounts of shipbuilders – to create a truly authentic representation. This painstaking research often reveals fascinating details that are absent from more generalized depictions. Building a ship from a detailed set of original plans becomes a form of historical detective work.

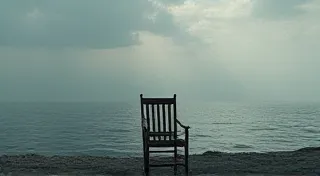

Beyond the technical aspects, the emotional connection to the past is perhaps the most rewarding aspect of building wooden model ships. It's a meditative process, a chance to slow down, to focus, and to connect with the generations of shipwrights and mariners who came before us. It's an opportunity to reflect on the complexities of history, to challenge conventional narratives, and to appreciate the profound human endeavor that is maritime exploration.

Ultimately, the compass rose of perspective is not about dismissing the accomplishments of the past; it's about understanding them in their full context, with all their nuances and contradictions. It's about recognizing the voices that have been silenced, the perspectives that have been overlooked, and the human cost that has often been ignored. And it’s through the quiet, deliberate act of building wooden model ships that we can begin to redraw that compass rose, charting a more accurate and empathetic course through the vast ocean of history.