Beneath the Surface: The Hidden Geometry of a Hull

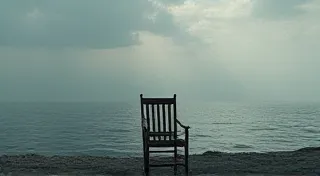

There’s a quiet reverence that descends when I’m working on a wooden model ship. It’s more than just the precise cutting and gluing, more than the careful layering of planks. It's a connection to centuries of maritime history, a feeling of tangible legacy. My grandfather, a quiet man who rarely spoke of his own past, taught me the basics. He's gone now, but the scent of pine and linseed oil in my workshop instantly transports me back to his small, cluttered shed, listening to his hushed explanations of how a seemingly simple hull could conquer the vast ocean.

Most people see a ship as a romantic symbol – adventure, exploration, the boundless horizon. But beneath that romantic veneer lies a meticulously calculated framework, a profound application of geometry designed to withstand the brutal realities of the sea. Building a wooden model ship isn't just a craft; it’s an act of deciphering a code, a chance to appreciate the brilliance of the naval architects who came before us. It's about understanding why things are the way they are, not just replicating how they look.

The Lines Plan and the Logic of Curves

The true genesis of a ship's form is found in the lines plan – a series of views showing the half-breadth plan (a side view), the body plan (a profile view showing decks), and the buttock plan (showing the shape of the bottom). These drawings dictate everything, from the shape of the stem and sternpost to the curve of the keel. These aren't arbitrary curves; they're the product of countless calculations, optimizing for speed, stability, and cargo capacity. Think of the graceful sweep of a clipper ship’s hull, designed to slice through the waves with incredible speed. That’s not mere aesthetics – that’s hydrodynamic efficiency, painstakingly engineered.

Early ship designs were, of course, largely empirical. Shipwrights relied on centuries of accumulated knowledge passed down through generations. They would observe how different hull shapes performed and refine their designs accordingly. There was a lot of trial and error involved, and many a ship was lost due to poor design. But as mathematics became more sophisticated, naval architects began to incorporate these principles into the design process. Figures like William Symonds, in the 20th century, pioneered the use of mathematical formulas to predict a ship's performance in the water.

From Theory to Timber: Translating Geometry into Wood

The challenge for the model builder isn't simply to reproduce the lines plan; it's to translate those complex curves into accurately shaped timbers. This requires a deep understanding of geometry and a mastery of woodworking techniques. The traditional method of building a wooden model ship – plank-on-frame – is incredibly demanding. Each plank must be precisely shaped to conform to the curve of the frame. This isn't a matter of simply cutting a plank to the right length; it’s about creating a three-dimensional shape that follows a complex curve.

The thickness of the planking is also crucial. Thicker planks provide greater strength, but they also add weight and reduce speed. The shipwright had to find a balance between these competing factors. That's why you'll often see variations in plank thickness along the hull – thicker at the waterline, where the stresses are greatest, and thinner towards the bow and stern.

The Beauty of Imperfection: Echoes of the Past

What’s fascinating is that modern computer-aided design (CAD) software can produce incredibly precise lines plans. Yet, the beauty of a handcrafted wooden model ship, especially those built using traditional methods, lies in its imperfections. Those tiny variations in plank thickness, the subtle distortions caused by the natural grain of the wood – these aren't flaws; they are echoes of the past, reminders of the human hands that shaped them.

My grandfather’s models weren’t perfect, but they possessed a certain charm – a tangible connection to the past that a perfectly rendered computer model simply couldn’s replicate. He often used reclaimed wood, each piece carrying its own history. He said the imperfections weren't mistakes, but stories etched into the grain – a reminder that even the grandest vessels are built from humble beginnings.

Beyond Replication: A Deeper Appreciation

Building a wooden model ship isn't just a hobby; it’s a form of preservation. By recreating these vessels, we’re not just preserving their physical form; we're preserving the knowledge and skills that went into building them. We’re also deepening our appreciation for the ingenuity and craftsmanship of the shipwrights who came before us.

And this extends to appreciating the history embodied within these models. Think of a model of a Napoleonic-era frigate, a floating embodiment of the political tensions and global conflicts of its time. Or a coastal schooner, reflecting the vital role these vessels played in trade and transportation. Each model tells a story, waiting to be discovered.

A Legacy in Wood

The process can be challenging, requiring patience, precision, and a willingness to learn from mistakes. But the rewards are immense. There's a quiet satisfaction in holding a finished model in your hands, knowing that you’ve recreated a piece of history, a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring allure of the sea. It's a legacy in wood, a tangible connection to the past, and a source of endless fascination.